Reflections on the Western U.S.A. Eritrea Festival 2014

Dr. Samuel Mahaffy

I came to the Western U.S.A. Eritrea Festival 2014 as an invited guest. I left as a family member being in the company of sisters and brothers from Eritrea, our shared distant homeland. The invitation to present as a speaker at the Festival surprised and delighted me. Yes, I have been public in my deep

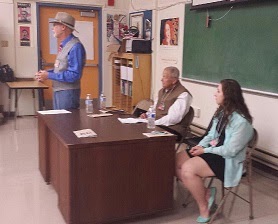

appreciation of the Eritrean people and culture. And, I have been relentless in maintaining that the invisiblization of Eritrea in the West—especially in the U.S.—is ill-conceived and unjust. Still, I came to the Festival as one of ‘The Other Eritreans.’ I was joined by Emilio DeLuigi, a delightful and distinguished Canadian-Italian gentleman and author of the book Ninety-Three Days: A Journey to Freedom. Between us on the panel, like a rose between two old thorns was Emilio’s articulate granddaughter, Elena. Our panel was moderated by Issayas Tesfamariam. Issayas’ remarks in a post-Festival communication to both Emilio and I mark the warmth of the relationships we deepened with Eritreans in Oakland. He notes that we are now accepted as The Other Eritreans with

‘no parenthesis.’ There was no bracketing of our experience of Eritrea because of our different heritage. It is reflective of the beautiful inclusiveness of Eritreans and their exquisite ability to warmly welcome others. We were fully accepted as part of the Eritrean family. I share here—in addition to my deep appreciation of this experience—what I learned at the Festival about Eritrea—its past and its future.

Mr. Emilio De Luigi, Dr. Samuel Mahaffy and Elena De Luigi.

Eritrea is often spoken of in terms of three distinct historical periods—pre-liberation, the struggle for Independence, and post-liberation. This differentiation unfortunately tends to minimize what has been consistently true of Eritrea and the Eritrean people over the decades and centuries.

From his first-hand experience of escaping out of Ethiopia through Eritrea, escorted and assisted by Eritrean liberation fighters, Emilio De Luigi expresses well that the post-liberation Eritrea was already being shaped and built during the struggle for Independence. The battle for liberation and the evolving re-birth of a free and independent Eritrea charting its own course were one and the same struggle.

De Luigi notes that the organization of the Eritrean liberation fighters was not the recruitment of a military or mercenary force. It was an organic movement. This was a compelling call answered by the people of Eritrea to free their country from outside dominance. It reflected the yearning of a people for freedom, independence and a promising future.

It occurs to me that this is, in fact, the most significant aspect of the way in which the United States and some other Western governments miscalculate in regard to Eritrea. Eritrea is here to stay precisely because it is not first a military organization now ruling a country. It is first of all a people fiercely independent and determined to build their own future. The Eritrea that never kneeled down to oppressors and against all odds won its costly struggle for independence is the same Eritrea that will never kneel down before an outside hegemonic agenda of dominance over its own development priorities.

“The legacy of the Eritrean freedom fighters was equality", De Luigi spoke this from his first-hand experience of traveling in the company of Eritrean liberation fighters on nighttime trails twisting through the highland mountains of Eritrea. He recalls a captured Ethiopian soldier joining him and the Eritrean liberation fighters in eating from a common dish. Rations of food were shared equally among the liberation fighters, their captured opposition fighter and their escorted guest.

Eritrea was already being shaped as a future society through the struggle for liberation. That shaping encompassed a vision for equality and respect for differences. Eritrean people of the Moslem faith and the Orthodox Christian faith, who once fought side-by-side for independence, now have houses of worship in the capital city of Asmara standing in sight of each other. Within a distance of less than two kilometers can be found a Moslem mosque, an Orthodox Christian church, a Catholic church, a Jewish synagogue and an Evangelical Lutheran church.

Many years after the struggle for Independence, the celebration of that great achievement still resonates and vibrates through the Western U.S.A. Eritrean Festival. It is a shared story that crosses generational lines and defines a spirit of both resiliency and joy so evident at the Festival. There is also evidence of a cautious guardedness. The struggle for liberation received little support from the outside world. The invisiblization of Eritrea and the unwillingness of other countries to embrace its hard-earned independence has left wounded relationships. The healing of these relationships will surely require mutual respect and patience.